For the series Camp Home (2007-2011), I documented the reuse of buildings from the Tule Lake and Heart Mountain Japanese internment camps, where members of my father’s family were incarcerated during World War ll.

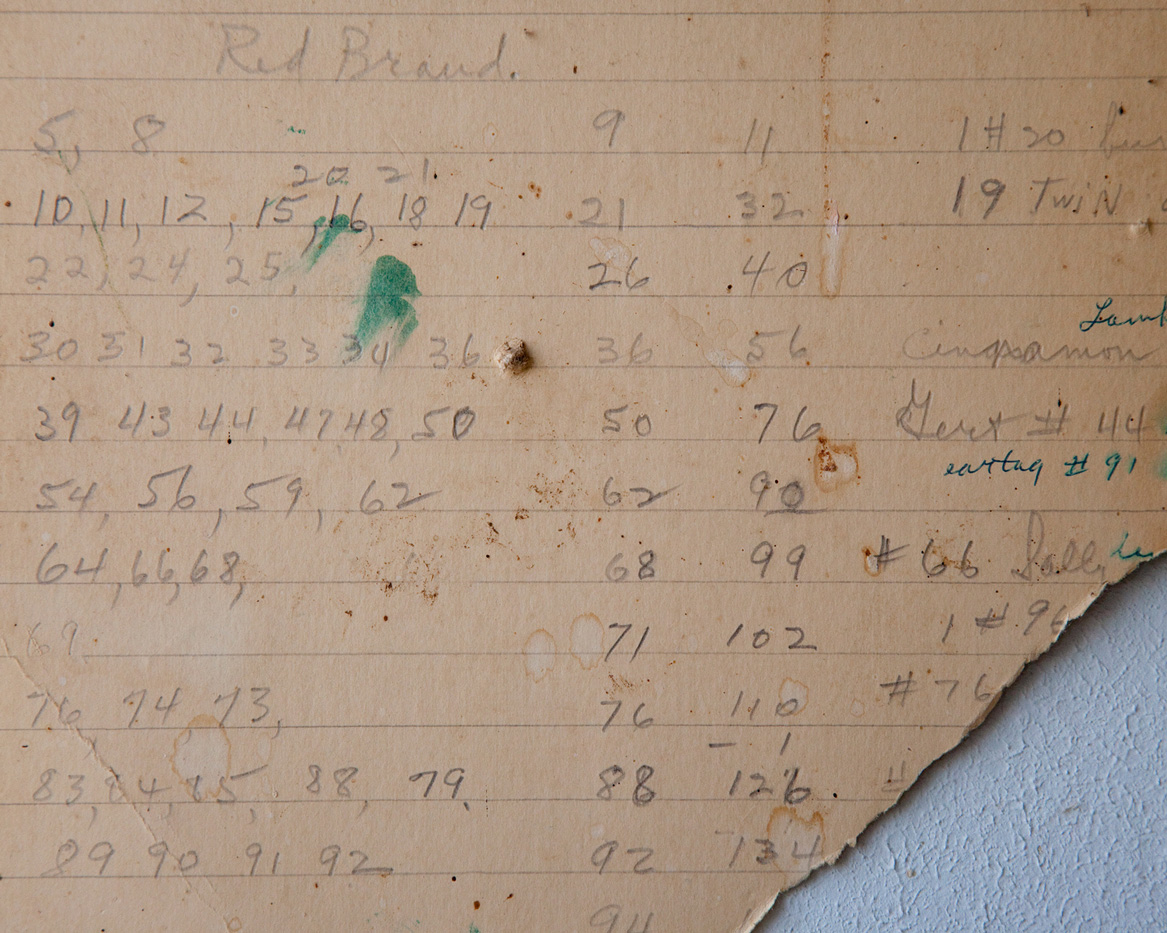

The barracks which served as de facto homes to internees at Tule Lake (in Northern California) and Heart Mountain (in Northwest Wyoming) were dispersed throughout the neighboring landscape following the war under a government-sponsored homesteading program. They were adapted into homes, barns and outbuildings by returning veterans (many of whom had fought in the Pacific theater) who used them as important physical elements in building their new lives.

I’m interested in examining the changing value of these institutional architectural forms. Buildings constructed as a result of wartime hysteria and racist attitudes became structures which helped to enable an American dream by another set of individuals.

The act of searching for the buildings and approaching their owners was important to my process. I’m seeking family history -- both my own and that of the current building owners -- and time was often spent sharing our own uniquely American stories. Family histories intersect and are connected by the history of these buildings, and by the lives lived within their walls.

The word “camp” is used by most Nisei, or first-generation Japanese Americans, to describe both the physical place they were held, as well as the overall wartime incarceration experience itself.

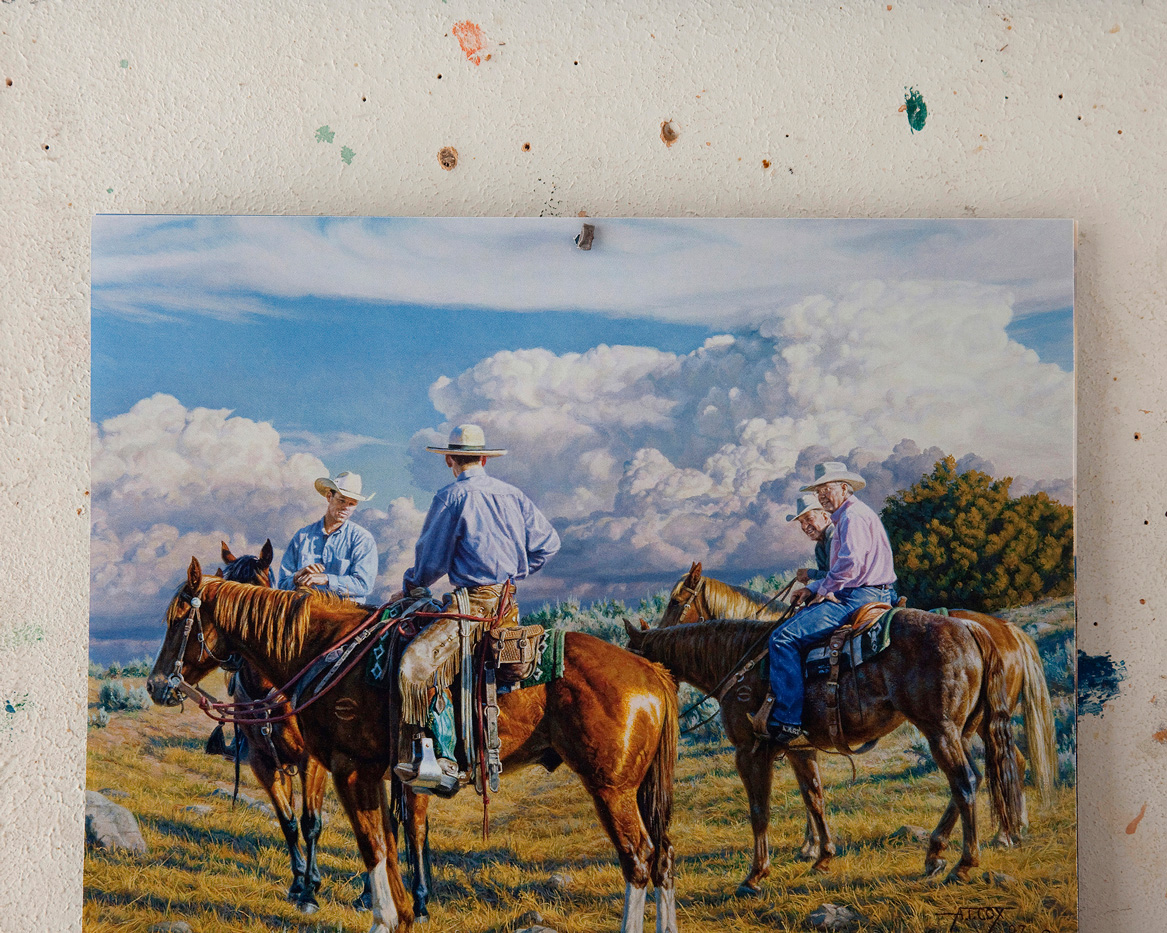

Historic Images: Top left: Housing for Japanese American families, Tule Lake, CA;

Top right: My father (left) with his sister and parents at Heart Mountain, the second camp they were incarcerated in; Bottom left: Barracks being moved to a homesteader's new property; Bottom right: A typical farm using several buildings from the camp at Tule Lake.